Cast an eye across any refined hunting party – or, perhaps, one of our beautiful seasonal campaigns here at Purdey – and there’s often one accessory that stands out among the sea of polished barrels, muted tweeds, patinated leather satchels and flamboyant garters: the country stick. Usually topped with the intricately-carved head of a native gamebird, it’s one of the most charming pieces in the sportsman’s inventory.

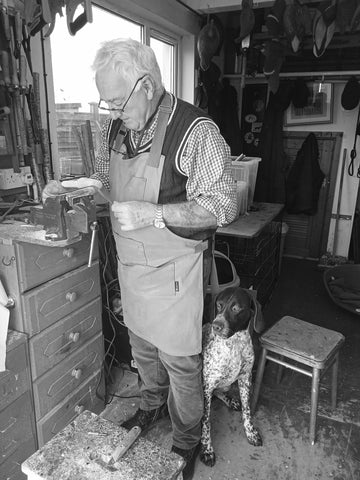

Ours are the work of one Robert McKergan, a hobbyist stick-carver turned artisan master, who creates small batches of sticks in his garage-workshop in Portstewart, County Londonderry. McKergan’s artistic trajectory wasn’t entirely conventional. After leaving school at 15, he worked as an electrician with his father, before moving to the petrochemical firm Monsanto (where he spent a year in a drafts office, learning to use lathes and the like) and then joining the police force. He’d always been a field enthusiast – training gundogs, hunting for snipe and woodcock, and making sporting forays to Yorkshire, South Ayrshire and the Western Isles – but the segue into stick-carving came with meeting another amateur woodworker in the force in 1989. “I said, ‘Would you not think about carving a mallard?’,” he recalls. “He says, ‘I couldn't do that.’ It put the notion in my head.”

McKergan began whittling his own sticks, gifting them to local farmers and landowners whose rough land he wanted to traipse, and the gamekeepers he worked with on grouse counts and shooting parties on the Scottish moors. “It was a thankyou to the gamekeepers,” he says. “A lot of them were running around with better sticks than the moor owners themselves!”

Thirty-four years later, McKergan’s aesthetic specialism remains wildfowl, gamebirds – anything he’s hunted, basically – and dogs. It helps, he explains, to carve from life, sometimes working to a physical bird after a shoot. “If it's something strange, like a pintail or a widgeon, I can look at the head and get the finer details,” he says. “You actually need that – to carve from a profile of a photograph, you're not seeing in below the bill or all the wee fine bits.”

That said, he’s seasoned enough to carve some designs with his eyes closed. “I could carve a mallard pretty much without looking at anything! Pheasants and red grouse, too.” Things are obviously a little different with the shorthaired pointers he occasionally fashions: “Here in my garage,” he laughs, “there’s probably just one lying at my feet.”

Every design starts with the wood. Provenance is all, and McKergan has always looked to his immediate surroundings for his materials. “First and foremost it’s availability. And for me, the first wood of natural choice was hawthorne,” he says, given his coastal home’s provision of the hardy perennial, which flourishes in spite of the salty sea air and interminable breezes, the natural contours of which he found alluring.

He’s since branched out (no pun intended) into a panoply of woods. The choice of material is still driven by pragmatism, but McKergan delights in utilising soft woods like ash, willow and sycamore (“The white grain looks good on the bills”), harder specimens like beech, oak and blackthorn, and even apple and pear when a trunk becomes available. Just what he’ll make is dictated by the curvature and dimensions of the living materials. “I look at a tree or a hedge, and see the shapes,” he explains. “I'm seeing pheasants, ducks, and things – the actual thing before it's even cut.”

He seasons the wood for anything up to three years to avoid cracking and shrinking – ”Say I need a piece six inches long, I would cut that up maybe three or four inches on each side of that again, just to allow for the seasoning” – before taking to it with his tools.

First, McKergan uses a saw and a wood rasp to bring his chosen branch down to size, before carving the finer details with a Stanley knife, and getting into the intricate feathering with an engraver or – a sole concession to modernity – a set of Dremel wood-carving bits. Instead of painting the heads, he uses a a range of light wood-stains sourced from the New Forest to afford a more textured effect, finishing them with an eight-hour dunk in his own blend of gunstock oil – turps to penetrate the wood, a light vegetable oil, and boiled linseed – and coating the shanks with yacht varnish. The average time he spends on a single stick is around 15 hours, and the result is a dashingly painterly object, as visually striking as it is robustly functional; a piece to treasure for a lifetime.

The dual sense of meditativeness and surprise is still what drives McKergan, now 69, in his craft. Stick-carving is not, he stresses, a money spinner; but it’s a sanative calling. “There are some days I start to carve and it's a chore. But after five or 10 minutes I find it difficult to leave! It's absolutely therapeutic.” Crucially, he concludes, no two days (or sticks) are the same. It’s still, all these decades later, a quiet voyage of discovery.

“It's the same subject matter, but they're all different. Numerous times I’ve started carving into a piece of wood and the green comes through, or it has spalting, and it comes out fantastic. I’ve started carving a mallard, and maybe find a wee issue with some of the wood, and the mallard turns into a teal! That,” he says, “is the joy in it.”